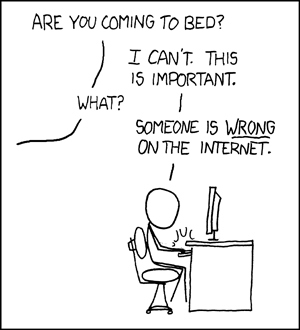

The best way of handling most things you don’t agree with on the internet is to simply ignore them, an approach that is much healthier than giving in and trying to correct every wrong and straighten every question mark you see. Considering how much dubious material there is on the internet (and elsewhere) about learning Chinese, I would surely die without this strategy.

Learn to read Chinese… with ease!

This is what I tried to do with ShaoLan’s Learn to read Chinese… with ease? and similar discussions about learning Chinese characters, but since I still receive recommendations to watch her TED talk (mostly from people who don’t study Chinese) and questions about the content (mostly from people who do study Chinese), I think it’s time to write a little bit about learning to read Chinese.

I’m not going to bash either ShaoLan’s TED talk or her product (which I haven’t seen); this has already been done by others. Instead, I’m going to address some questions related to the content of her talk. I’m also going to expand on my answers and discuss how some of the difficulties with learning to read Chinese can be overcome. Please note that even though I use ShaoLan as an example here, what i say ought to apply to a lot of other people and products as well.

First, let’s have a look at her TED talk, which is only six minutes long:

Learn to read Chinese… with ease?

In general, I think being encouraging and optimistic about language learning is good, even if some difficult and depressing facts are ignored or brushed over. This is especially true for Chinese, which has earned a reputation for being impossible to learn, which is evidently not true. Even though I think the claim that learning to read Chinese is easy while learning to speak is hard, is exactly opposite to most people’s experience, I’m not going to dwell on speaking Chinese now.

Instead, I want to address an issue which is common in lots of product introductions and advertisements (not just the above TED talk), namely that of numbers relating to reading ability in Chinese. The claims are different in different sources, but these are from ShaoLan’s talk:

- A Chinese scholar knows 20000 characters

- 1000 characters will make you literate

- 200 characters to read menus, basic web pages and newspaper headlines

- Chinese characters are pictures

I’ll address these one by one. In some cases, there are no exact answers, but I’ll try to provide different points of view here, as well as my own opinion.

Chinese has a bazillion characters

For some reason, it’s quite popular to first scare students and say that there are 20000 or 50000 characters, making Chinese sound impossible. Most Chinese scholars certainly don’t know 20000 characters. That’s a ridiculously high number and the only ones who will stand a chance of reaching that are people who spends serious time focusing only on learning as many characters as possible. Divide the number by three and you get closer to the number of characters educated Chinese people actually know.

You don’t need that many characters to read Chinese

The next step is to make the amount of character you actually need to learn sound really low. It sounds much better to go from 20000 to 1000 than from 6000 to 3000, doesn’t it?. There are different numbers, but I think 2000 is the most common one, but ShaoLan chose 1000. Whatever the number is, it’s usually followed by a percentage telling you how much you can understand of Chinese text knowing that many characters. In the case of 1000 characters, it’s 40% in the video.

The problem is that any such comparison is completely meaningless. In Chinese, meaning is conveyed using words and most words consist of two characters. Thus, knowing a certain amount of characters isn’t directly related to reading ability at all. For instance, if you know that 明 means “bright” and 天 means “sky” you will have no idea that 明天 means “tomorrow”. This is not apparent from the constituent parts of the word.

Furthermore, even if you did know all words that could be created with all the characters you know, it still wouldn’t tell us much about your reading comprehension. The problem is that if you know the most common 1000 characters, you’re bound to know a lot of common pronouns, nouns, verbs and particles. However, these are rarely the key vocabulary in a sentence. Knowing 50% of the words in a sentence does not give you 50% reading ability. It might actually get you 0% reading ability in some cases and perhaps even more than 50% in others. Unless you’re reading fiction where there’s a lot of fancy adjectives and adverbs, I think not knowing key components in a sentence tends to reduce reading comprehension a lot more than the percentage of characters you know implies.

Apart from this, there’s also grammar, word order and a lot of other things to learn which aren’t related to the number of characters you know either. To sum things up, learning a certain amount of characters will have little direct effect on reading ability (although the indirect effects can be substantial).

200 characters to read newspaper headlines?

This claim is somewhat unique for ShaoLan, I think, and I have no idea where she got this from. In my experience, headlines are often the trickiest part of a newspaper article. When I took a course in newspaper reading in 2009, we usually saved the title until after we read the article because it only made sense for us when we already knew the story. 200 characters won’t take you close to understanding newspaper headlines, 2000 probably won’t either.

The same is true for menus, but in a different way. The problem (at least for me) with menus in Chinese is that there are so many characters that are only used for food. I don’t really care that much and haven’t bothered to learn all these characters, so I find menus confusing even though I can write about 5000 characters. Approaching a menu with the 200 most common characters will probably only give you hints for a small part of the menu and will most likely only tell you if it’s rice, noodles or soup. If you’re lucky, you might be able to deduce what animal has died to provide your meal.

It would be interesting to take a few menus and see how many of the characters on them fall within the 1000 most common characters. If you have a menu and some spare time, feel free to contribute! Let’s use this list for frequency data. If you want to know more about roughly what you need, you can start with this article over at Sinosplice.

Chinese characters aren’t pictures

I’m sorry to say this, but Chinese characters aren’t pictures. Yes, there is a (very) small percentage of characters that originally directly represented objects in the physical world, such as 日 “sun” and 月 “moon”, but these characters make up a small fraction of characters in use today. I have a several books that teach Chinese characters through pictures and the problem with all of them is that they are mostly cherry-picking easy characters that make good pictures.

You can probably learn a few hundred characters this way, but the problem is that the characters you learn this way are not going to be the most frequently used characters. For instance, while it’s true that 囚 means “prisoner”, this character doesn’t appear in the most commonly used 2500 characters and will help little to increase your reading ability. The same is true for 姦, which is actually a traditional character (simplified as 奸).

This reminds me of something else. If you’re learning Chinese, you should choose to learn either traditional or simplified characters and stick to one set until you know it relatively well (it doesn’t really matter which you choose). You can learn both sets later and it’s not very hard, but choosing one or the other on a character-by-character basis because one might be easier to recognise than the other is not a good idea (for instance, ShaoLan uses traditional 姦 but simplified 从).

Learning to read Chinese is not easy

This should come as no surprise to anyone who has learnt to read Chinese. Still, the point with this article isn’t to discourage you and say that Chinese is impossible to learn either, but I do think a that a measure of realism is needed. Learning a hundred pictographs and combinations of such isn’t all that hard and there’s nothing really new with that method.

But what about the rest? What about the remaining 3000 characters you need to approach actually literacy? Here are a few things you can do to boost your character learning and make learning Chinese possible, although it will still take a lot of time:

- Most Chinese characters (around 80%) are combinations of meaning and sound. Learn how these characters work and you will save yourself a lot of time and trouble. I have written two articles about this:

Phonetic components, part 1: The key to 80% of all Chinese characters

Phonetic components, part 2: Hacking Chinese characters - Use clever memory techniques (mnemonics) to learn characters. This is not something new, it’s been practised basically forever, but our understanding of why and how mnemonics work has improved immensely. I have written about this many times:

Memory aids and mnemonics to enhance learning

Remembering is a skill you can learn

Creating a powerful toolkit: Character components - Don’t rely on rote learning if you can avoid it. There are some thing you will have to rely on brute force to learn and that’s okay, but whenever you can, try to make learning meaningful. If you want pictures like those used in the TED talk above, Memrise is a good place to start (it’s also free). In any case, avoid rote learning. It might work, but it’s horribly inefficient.

You can’t learn Chinese characters by rote

Holistic language learning: Integrating knowledge

Conclusion

Learning to read Chinese is not impossible, but it’s not easy either. Exactly how difficult it is depends on a lot of factors, some of which are beyond your control, but ShaoLan definitely has a point when she argues that learning Chinese needn’t be as hard as people think. Personally, I don’t like the way she does it, it looks way too much like someone trying to sell a product regardless of the truthfulness of the sales pitch.

Moreover, cherry-picking examples to prove your point isn’t very good, although I have made myself guilty of that as well. Still, if this makes people just a little bit more optimistic about learning Chinese, making them start learning the language or keep on studying even if it feels impossible at times, I’m not really complaining.